Aboriginal gambling: a question of addiction or resource redistribution?

By Martin Young; Bruce Doran, Australian National University, and Francis Markham, Australian National University

“Aboriginal gambling” has become something of a hot-button issue in recent years. A number of academic research articles have documented the “risk factors” for Aboriginal people that increase their likelihood of develop gambling problems – enough to justify a recent overview paper by the Centre for Gambling Education and Research at Southern Cross University.

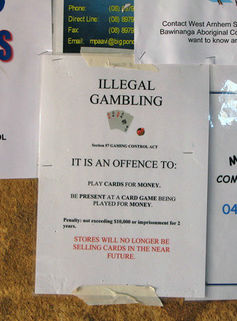

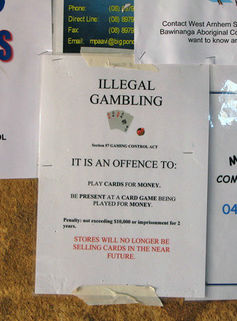

Governments have not been lax in responding to the perceived evils of Aboriginal gambling. Gambling was one of four goods and services that the 2007 Northern Territory Intervention explicitly banned for the purposes of income management. Police in one remote NT community reportedly posted notices stating that it is an offence to gamble with cards, or even to be present at a card circle.

While gambling may be associated with many negative impacts for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and communities alike, it is easy to suggest that gambling is just one more problem associated with “dysfunctional” remote communities that need to be “normalised” and brought into line with white mainstream expectations.

Yet accounts of Aboriginal card games in remote communities offer a different perspective, one that reveals complexity and belonging within local social processes. For example, in a 1985 study, ANU anthropologist Jon Altman reported that card circles played an important structural role in the community.

This positive social and economic role has been noted by subsequent studies. Card games have the potential to circulate money among kin in a generally positive way to enhance equality, social cohesion and the ability to accumulate resources for expensive purchases.

Christie et al.

When poker machines are added to the mix, gambling resources are redistributed in a completely different way. As the “house always wins” with pokie gambling, the net effect is a transfer of resources out of remote communities and into the casinos and other pokie venues. As such, pokie venues in the NT have been demonstrated to be sites of economic exploitation, which redistribute resources from the poorest in society to governments and gambling businesses with remarkable efficiency.

The catchment of Lasseters Hotel Casino at Alice Springs, for example, spans over 800 kilometres and draws most of the Aboriginal communities of Central Australia into its orbit. The monies harvested flow to the Malaysian-owned Lasseters Corporation, with taxation receipts going to the NT government in Darwin.

Regardless, casinos are increasingly popular among Aboriginal people in the NT, in part because they provide a more welcoming environment than other public spaces. In both Alice Springs and Darwin, occupation by Aboriginal people of sites of consumption such as public shopping malls is highly regulated and subject to discriminatory policing.

The card games that used to occur in public space have now been largely quashed, through either redevelopment or regulations that allow police or council rangers to “move on” gamblers in public areas.

In this context, commercial gambling spaces (such as pubs, clubs and casinos) have emerged as one of the few quasi-public spaces for Aboriginal social inclusion. Pokie venues serve specific social needs by providing a space in which cash and company can circulate in an exciting, comfortable and secure air-conditioned environment.

It was these positive, enjoyable aspects of the casino space that Aboriginal participants in our Alice Springs research study emphasised.

So, what then is the problem of Aboriginal gambling in the NT? Do we need to focus on gambling addicts and find ways to curb their behaviour (as per the NT Intervention)? Or do we look to try to mitigate the ways in which pokie venues exacerbate the economic impoverishment already experienced by remote communities? We argue for the latter.

One simple idea may be to give Aboriginal people more of the profits from gambling venues. This already happens in the United States, where in 2010-11, over 200 Indian nations owned 421 casinos, raising more than US$27 billion in revenue.

Indian casinos have succeeded in substantially raising living standards for some Native American groups where governments have failed. However, these casinos have only been possible in the United States because Indian land is exempted from the jurisdiction of state legislatures, a situation that is difficult to imagine in Australia.

In Canada, however, successful lobbying by First Nations paved the way for the establishment of profitable Aboriginal-owned casinos in almost every Canadian province, without recourse to sovereign rights.

Rather than redistributing funds away from Indigenous communities – as is the case with casinos in Australia – the development of “tribal casinos” has been the most successful form of Indigenous economic development in the United States. Profits from casinos have benefited community development and are directed by Indian nations themselves towards locally determined goals.

Bruce Doran

In an era of “evidence-based policy” and hand-wringing about remote economic development, we might expect policy experts and governments to be keenly discussing the American model. But as the University of Queensland’s Fiona Nicoll points out:

… the situation in Australia could not be more different … Indigenous people are rarely imagined as potential owners or as direct beneficiaries of gambling revenue and the issues raised by gambling businesses are almost always considered in relation to consumption.

A less radical alternative is to give Aboriginal groups more control over individual gambling venues. While not providing for the same level of economic development, local ownership and control of Aboriginal pokie machine venues in the NT may provide a feasible opportunity to mitigate the regressive political economy of poker machine gambling.

Local ownership and control might allow for the positive aspects of card gambling – in terms of the accumulation of funds – to be reimagined in community terms. Profits could be used for purposes decided by the community itself.

At the same time, local ownership would retain the attractive features of poker machine venues: their ability to provide exciting, welcoming and comfortable quasi-public spaces in towns with few alternatives.

Given that Aboriginal people already support some poker machine venues financially but realise none of the profits, a change in ownership would do little additional harm and would return funds to the communities from which they were extracted.

Aboriginal gambling venues would not be a silver bullet to eliminate all the negative consequences of pokie gambling for Aboriginal people. For individual gamblers, it would continue to be associated with the same harms associated with existing venues.

However, what an Aboriginal-controlled gambling venue would provide is some measure of local control over the use of gambling losses, and the ability to institute harm-minimisation measures that are culturally appropriate to Aboriginal ways of gambling.

Essentially, there should be a transfer of responsibility for gambling to local groups, both in terms of its financial benefits and its associated harms. The alternative – to simply do nothing – will merely continue to see gambling funds siphoned away from Aboriginal communities in the NT.

This is part two of a two-part feature on Indigenous and remote gambling in Australia. You can read part one here.

![]()

This article draws on a recent chapter by the authors: Young, M., Markham, F. and Doran, B. (2013) Gambling Spaces and the Paradox of Aboriginal Social Inclusion. In "In Black and White: Australians all at the Crossroads", R. Craven, A. Dillon and N. Parbury, eds., pp. 275-286. University of Western Sydney: Centre for Positive Psychology Education.

Martin Young is the lead investigator on ARC Linkages Project LP0990584: Gambling-Related Harm in Northern Australia. In addition to his SCU position, he is an Honorary Fellow at the Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, and a Visiting Fellow, Fenner School of Environment and Society, ANU.

Bruce Doran was part of a research team that was given funding from Australian Research Council for a project looking at remote area gambling impacts (ARC Linkages Project LP0990584: Gambling-Related Harm in Northern Australia).

Francis Markham does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Special populations and addictions will be discussed at Addiction2015 conference.