WHO report maps global suicide problem for the first time

By Reema Rattan, The Conversation; Emil Jeyaratnam, The Conversation, and Warren Clark, The Conversation

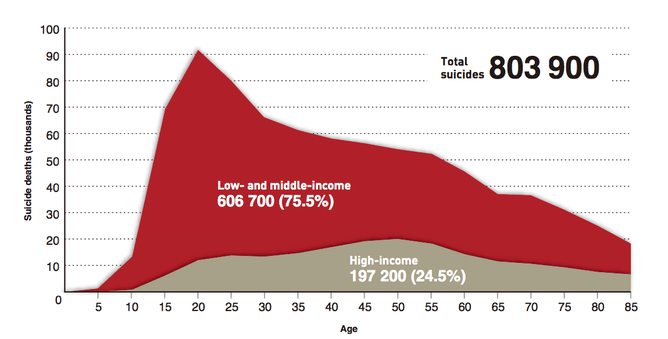

One person takes their own life every 40 seconds, equating to 803,900 deaths across the world every year, according to the first World Health Organization report on suicide prevention released today. “Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative” calls for co-ordinated action to reduce suicide worldwide.

Diego De Leo, director of the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention at Griffith University, who was involved in the preparation of the report, said there had not been any previous reports because suicide was an example of negative behaviour rather than a disease, so it did not fall within the jurisdiction of an international entity.

“But this is a fundamental step before we can begin on worldwide suicide prevention,” he said.

The report shows suicide is the second-leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year-olds across the world.

Professorial fellow in mental health at the University of Melbourne, Tony Jorm, said suicide stands out in this group because the general death rate is quite low in the young.

“If you’re dealing with older people you get cancer and heart disease as major causes of death but these are very rare in young people because they’re physically healthy,” he said.

But De Leo added that this was the age when people had to build their lives and that, coupled with a lack of experience, made them more vulnerable.

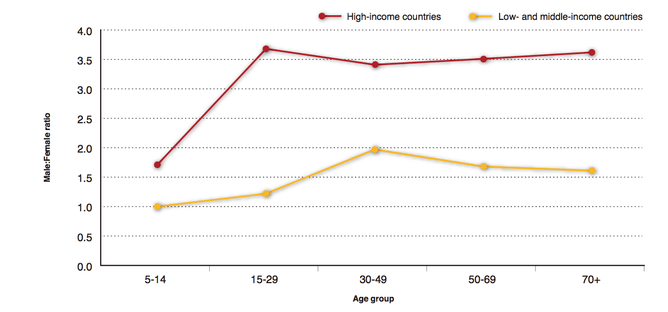

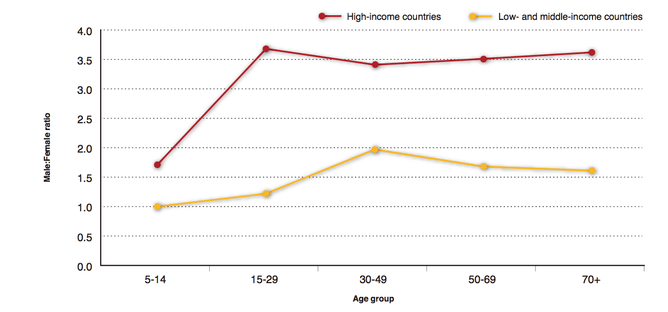

The report also showed men were more likely to die by suicide than women, especially in developed countries where they were three times more likely to die at their own hands.

WHO

Jorm said suicidal thoughts among women were more common in developed countries, but men were more likely to act on such feelings and thoughts.

“Men tend to be more impulsive than women so they are more likely to die by suicide,” he said. “They’re also more likely to use lethal methods so they’re more likely to die on their first attempt.”

De Leo added that in poor countries, the number of women who died by suicide was often higher.

“In many developing countries, young women of marital age are subject to a lot of pressure,” he said. “They may be forced into marriages that they’re not able to tolerate or face abuse that may render their life hell so their suicide rate is higher.”

Jorm said differences in suicide rates reflected social expectations and gender roles that needed to be looked at on a country-by-country basis, and socioeconomic issues also played a role.

“In Japan, for instance, the global financial crisis and its impact on unemployment had a drastic effect on the suicide rate in males,” he said. “There are a whole lot of specific factors in particular countries that are important, and then there are very general things across countries.”

WHO

The report lists a number of measures that governments can take to prevent suicide including responsible media reporting of suicide, policies to reduce harmful alcohol use, follow-up care for people who have attempted suicide, and restricting access to the means of suicide.

“A New Zealand study found that shifting the car park at a jumping point back further so you had to walk to the point reduced the suicide rate from that spot because people had time to reflect,” Jorm noted.

“If people are going to do it impulsively because something bad has happened, and if they don’t have the means readily available, suicidal thoughts are more likely to reduce. But if people have a long-term plan and are feeling suicidal over a long period, it might be quite a different situation.”

De Leo said suicide prevention needed a whole-of-society approach.

“We need education, employment, social welfare – all working together in a coordinated manner. Then you may reduce the impact of financial difficulties, relationship problems and unemployment and all the other things that lead to suicide,” he said.

Jorm agreed.

“You need to look at factors in society that place people in distressing long-term adverse circumstances and reduce those,” said Jorm. “But you also need to work at mental disorders because people can feel suicidal when they are not in those adverse situations. There are internal and external factors and you have to target both.”

If you have depression or feel very low, please seek support immediately. For support in a crisis, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 in Australia. For information about depression and suicide prevention, visit beyondblue, Sane or The Samaritans.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.